This op-ed by Vice President of the MacArthur Fellows program Cecilia Conrad was originally published in The Huffington Post on May 28, 2015.

About 1.8 million students will graduate from American colleges and universities this month, but their future trajectories will not be determined by the name of the school printed on their diploma. What also matters is the student’s active engagement in the educational experience. As the title of Frank Bruni’s recent book proclaims, “Where You Go Is Not Who You’ll Be.” Bruni’s book offers examples of luminaries, including several MacArthur Fellows, who did not attend the upper echelon of colleges and universities, but who excelled because they fully exploited the opportunities available at the institutions they attended.

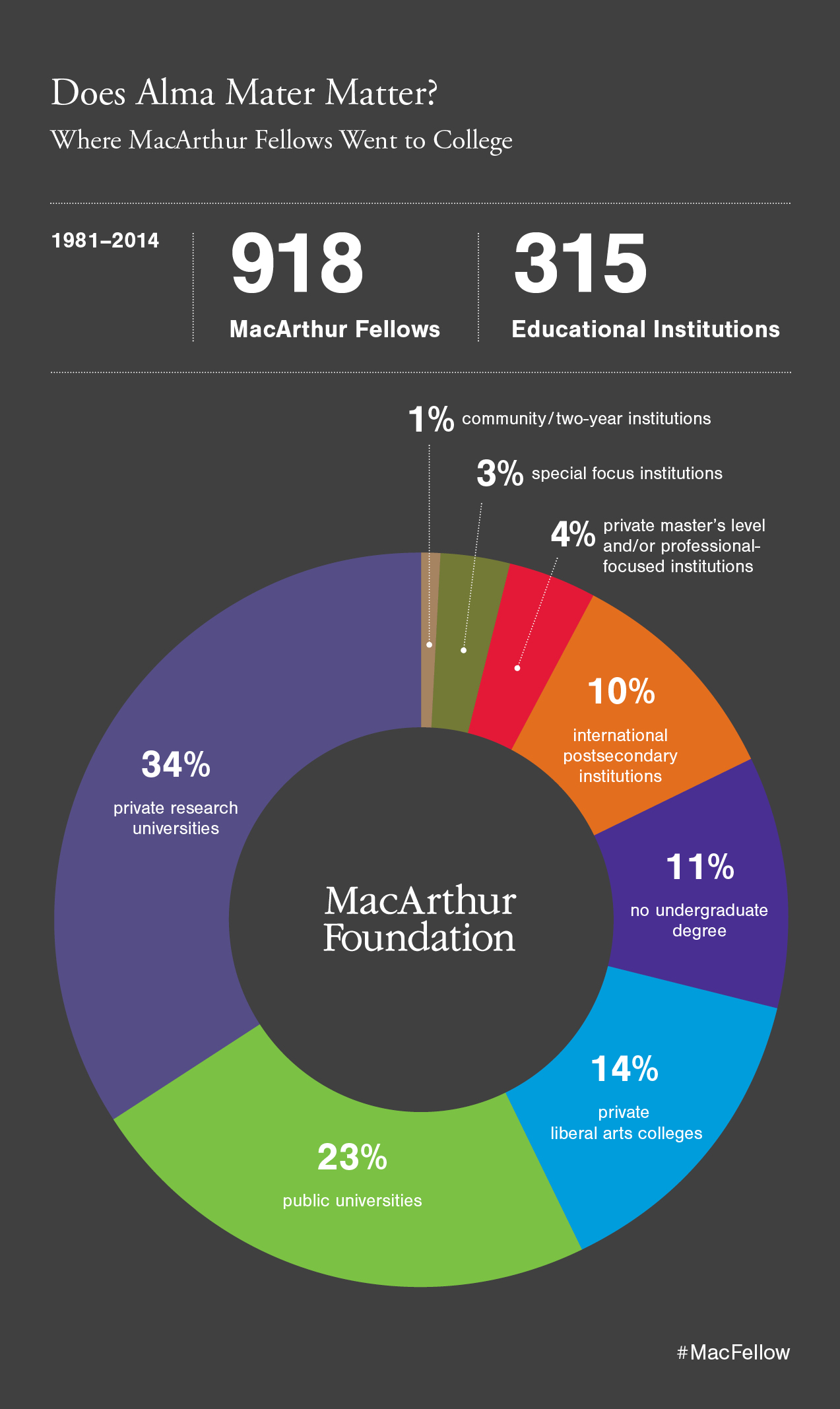

Newly compiled data on the educational background of MacArthur Fellows corroborate Bruni’s basic claim. MacArthur Fellows graduated from both private and public universities, from engineering schools, specialized colleges in art and music, and a school of theology. While the largest number of Fellows from a single institution graduated from Harvard, others attended less selective institutions. One in five Fellows graduated from institutions with acceptance rates of over 50 percent. Fifteen graduated from either historically black colleges and universities (HBCU) or tribal colleges and 44 from women’s colleges. Forty graduated from religiously affiliated institutions. Several Fellows, such as organic chemist Phil Baran, began their studies at community colleges. The 918 MacArthur Fellowship recipients attended 315 diverse post-secondary institutions.

And, there are a few MacArthur Fellows who did not attend college or did not complete an undergraduate degree. Writers Cormac McCarthy and Jonathan Lethem dropped out of college. Community organizer and youth activist Lateefah Simon went to Mills College after receiving the Fellowship. Musician Dafnis Prieto and silversmith Ubaldo Vitali did not pursue higher education. While country doctor D. Holmes Morton did earn degrees in higher education, he was a high school dropout who gained admission to college by taking correspondence courses while serving in the U.S. Merchant Marines and the U.S. Navy.

Our data provide one clue as to the educational environments most conducive for creative minds to develop: the relatively high number of Fellows who graduated from liberal arts colleges. Liberal arts colleges are distinctively American institutions, typically small, that focus on undergraduate education. Less than two percent of U.S. college graduates graduated from a liberal arts college, but 14 percent of MacArthur Fellows did. Liberal arts colleges are a diverse group of institutions. Some are highly selective; others are not. The category includes women’s colleges like Barnard College, which has produced ten MacArthur Fellows, including Irene Winter, an art historian who studied anthropology as an undergraduate. The category also includes church-affiliated colleges like Siena College in Albany, New York, where writer William Kennedy graduated, and historically black colleges like Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, where physician and scientist Donald Hopkins graduated. Liberal arts colleges share a common emphasis on close faculty-student interaction, quality teaching, and a curriculum grounded in the liberal arts. (In our data, we identified liberal arts colleges using the Carnegie classification system.)

By exploring why liberal arts colleges have produced a disproportionate share of MacArthur Fellows, we might gain insights into how to incubate exceptional creativity more broadly. It seems unlikely that liberal arts colleges admit more creative people than other colleges and universities. They rely on the same admissions criteria as other schools – standardized test scores, grade point average, and teacher recommendations – and those traditional metrics probably exclude those with the most creative potential. It is more likely that private liberal arts colleges have produced more than a proportionate share of Fellows because of the educational environment at those institutions. Something must be more likely to happen to a student at these institutions than at other institutions that allows creativity to flourish. I argue that something is a true liberal education.

The prerequisites for the exceptional creativity that characterize MacArthur Fellows align closely with the definition of a liberal education. Creativity requires basic competency in a broad array of disciplines, advanced competency in one or more fields, and the ability to make connections across fields so as to pose new questions or formulate new answers. It requires exposure to diverse perspectives, methodologies, and concepts of evidence. A liberal education equips individuals with the ability to deal with complexity and change. A high priority is placed on the development of critical thinking skills and the abilities to distinguish opinions from facts and to discern good ideas from bad. Ellen Browning Scripps, for whom Scripps College is named, may have best summed up the goals of a liberal education: “The paramount obligation of a college is to develop in its students the ability to think clearly and independently and the ability to live confidently, courageously, and hopefully.”

Although many institutions espouse the values of a liberal education, liberal arts colleges adhere more closely to those values than other colleges and universities. Some characteristics of liberal arts colleges are unique to those institutions. The high faculty-student ratios support deep interactions between professors and students both inside and outside of the classroom. Small class sizes are conducive to discussion-based rather than lecture-based pedagogy. Tenure decisions are based on a professor’s skill as a teacher as much as on his or her research productivity. Without graduate students, full-time faculty teach introductory courses, and undergraduates assist professors on research projects.

Other practices are not unique to liberal arts colleges but are more prevalent on those campuses. Students at liberal arts colleges are more likely to live all four years in a campus residential hall. Not only do residence halls encourage engagement with other disciplines and fields outside of the formal classroom, they also bring together students from diverse backgrounds. An economics major might join his geology roommate on a weekend hike or have lunch with a faculty member from history. A student from a small midwestern town may live with a student from Beijing, China. These peer-to-peer interactions with persons from different disciplines or different cultural experiences have been found to stimulate creativity.

At larger universities, it can be tricky to take courses outside one’s college or school and there may be little flexibility in the courses that satisfy general education requirements. Liberal arts colleges actively encourage coursework outside the major, in some instances capping major requirements to ensure that students have the space for interdisciplinary work. Universities tend to segregate students by domain, even in required courses, so that, for example, science majors take a writing class designed for, and only with, other science majors. At liberal arts colleges, by contrast, a physics student is very likely to take a course in Shakespeare or poetry with English majors and an English major would be exposed to biology or chemistry with science majors. Though most colleges and universities impose requirements on the distribution of courses taken, liberal arts colleges offer students considerable leeway in the selection of specific courses and activities. This freedom can help students develop the capacity to recognize and exploit situations in which their content knowledge or cognitive style differs from the norm in a field or discipline. An individual with an unusual skill set for a specific domain might be in the best position to come up with a truly new idea. Psychologist and MacArthur Fellow Howard Gardner and his collaborators have labeled this “fruitful asynchrony” and identify it as a precursor to exceptional creativity. Liberal arts colleges probably tolerate asynchrony more than other institutions.

Creativity requires giving self-directed original thinkers space for the missteps and dead ends that are often prerequisites for groundbreaking work. That is the philosophy behind the MacArthur Fellows Program and its “no strings attached” grants of $625,000. It is also a value embedded in the curriculum at liberal arts colleges, but these “creativity-promoting” educational values are not unique to liberal arts colleges. Many private universities offer similar opportunities for cross-disciplinary study and engagement. Honors Colleges or Colleges of Arts and Science within public universities encourage both depth and breadth of study. For example, as an undergraduate at SUNY-Albany, MacArthur Fellow Sheila Nirenberg planned to be a writer, but she took a class in human genetics as an elective and that led her to switch to a psychology major. She eventually became a neuroscientist working on prosthetic eye devices. Even if the academic program does not permit taking courses in different fields, an ambitious student will have opportunities for exploration through co-curricular activities, talks and lectures, exhibitions, musical performances, and plays.

A college education, like a savings bond, is an investment, but unlike other investments, a college education’s value depends on the active participation of the student. A student can construct a liberal education that promotes the development of creativity at almost any institution. It is incumbent on the student to move beyond his or her comfort zone, to make the most of the opportunities available; there will be many, regardless of the institution’s reputation. Undoubtedly, having a diploma from an elite college confers some advantages, but ultimately college is what you make of it. As the hundreds of MacArthur Fellows have shown, creativity flourishes at many types of institutions.